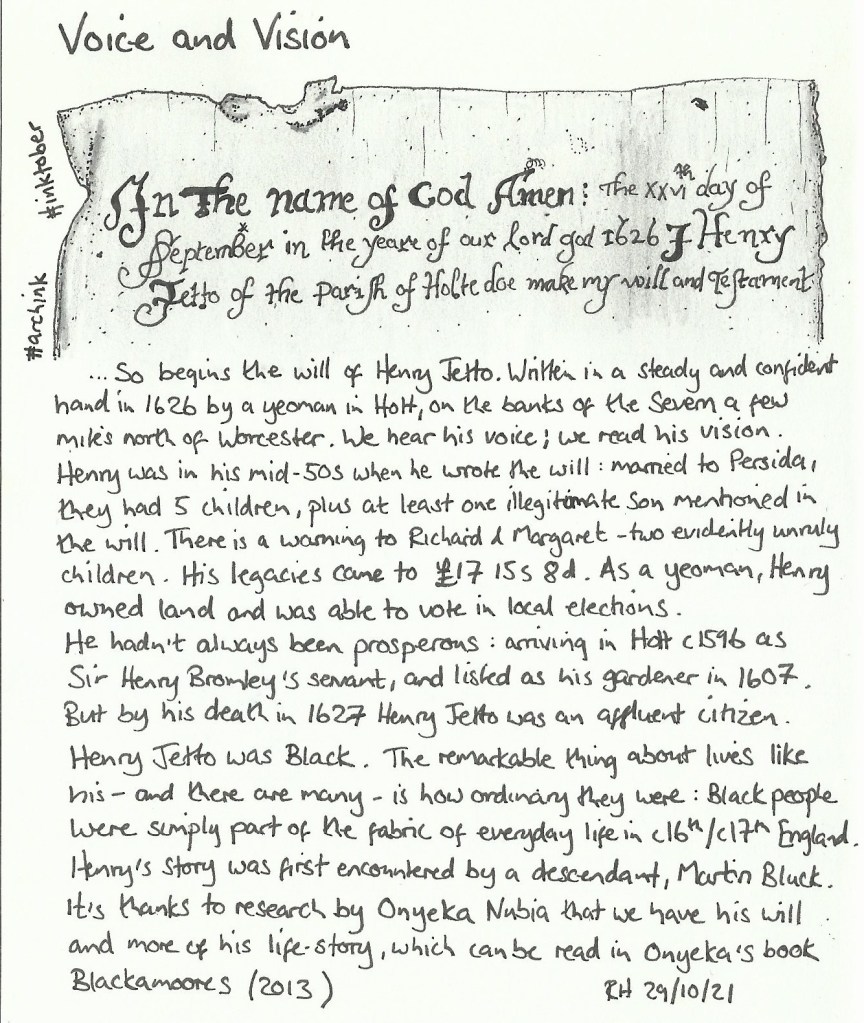

Just before Christmas, I headed up to Chester on my annual pilgrimage to TAG – the Theoretical Archaeology Group Conference. Hosted by a different University Archaeology department each year, the conference attracts around 400 archaeologists, chiefly from Europe and the USA, with a high proportion of speakers in the early stages of their careers.

The majority of delegates are based within — or affiliated to — universities. But there’s also a sprinkling of independent researchers, public sector archaeologists, commercial archaeologists… and those, like me, whose work and interests straddle multiple categories. In fact, at this year’s TAG, over 180 different institutions were represented.

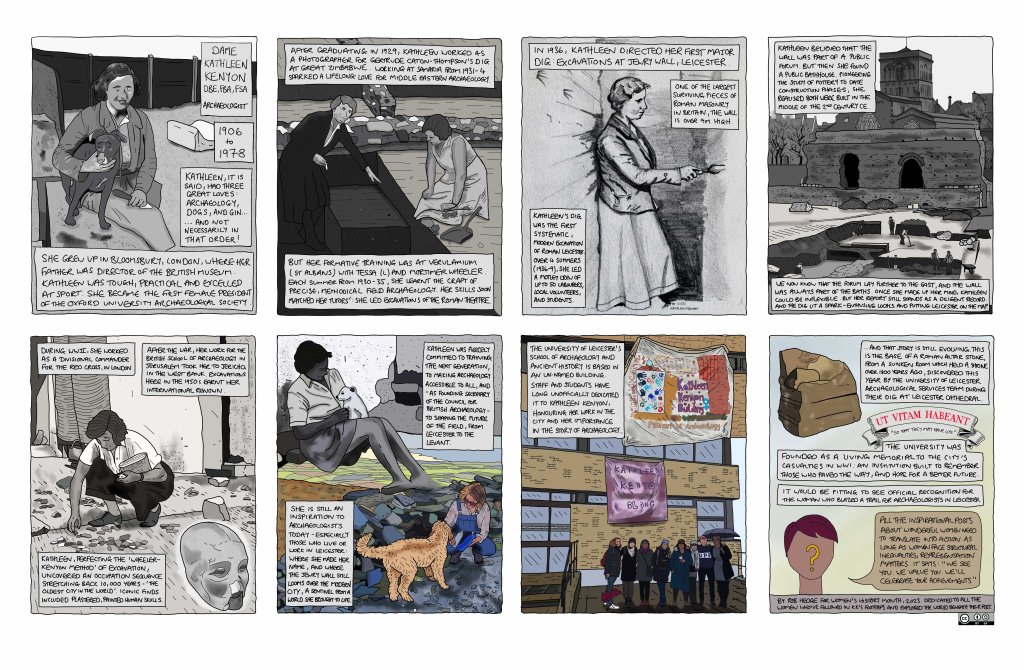

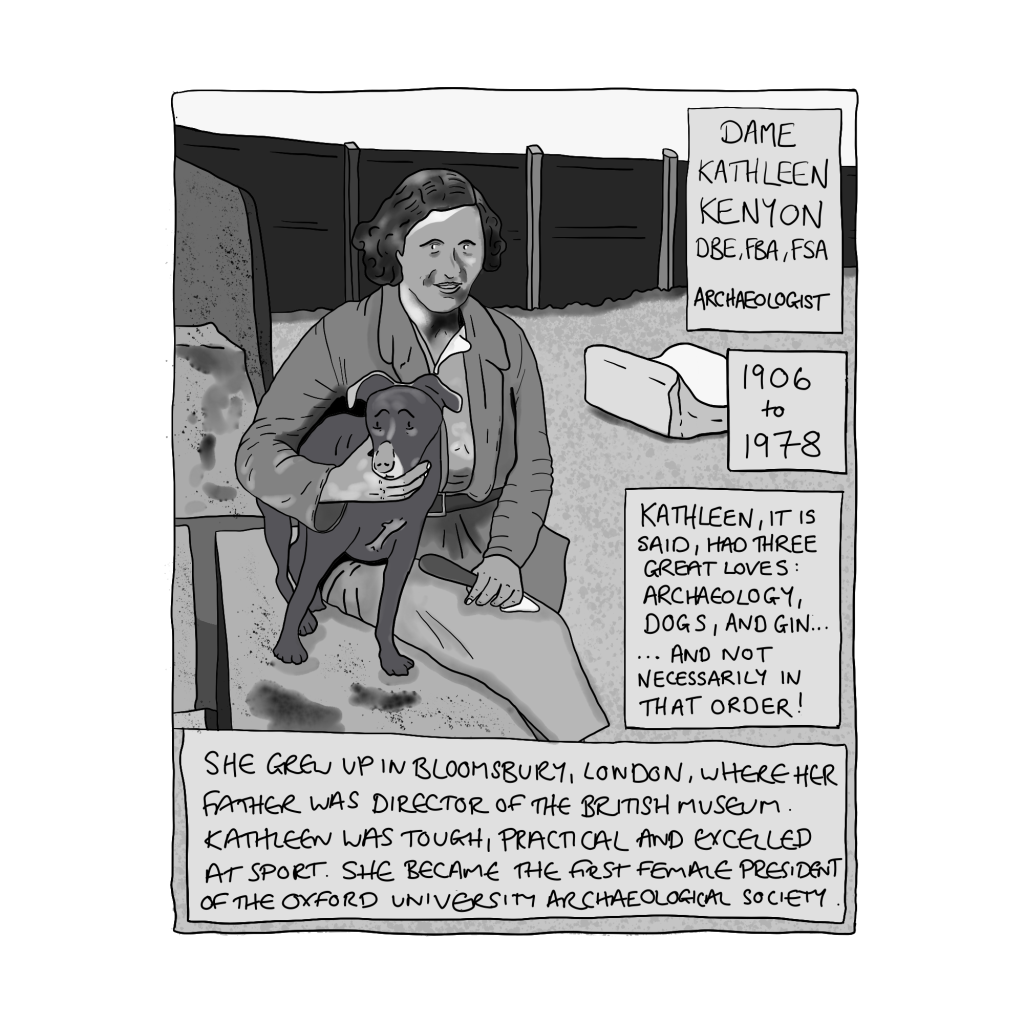

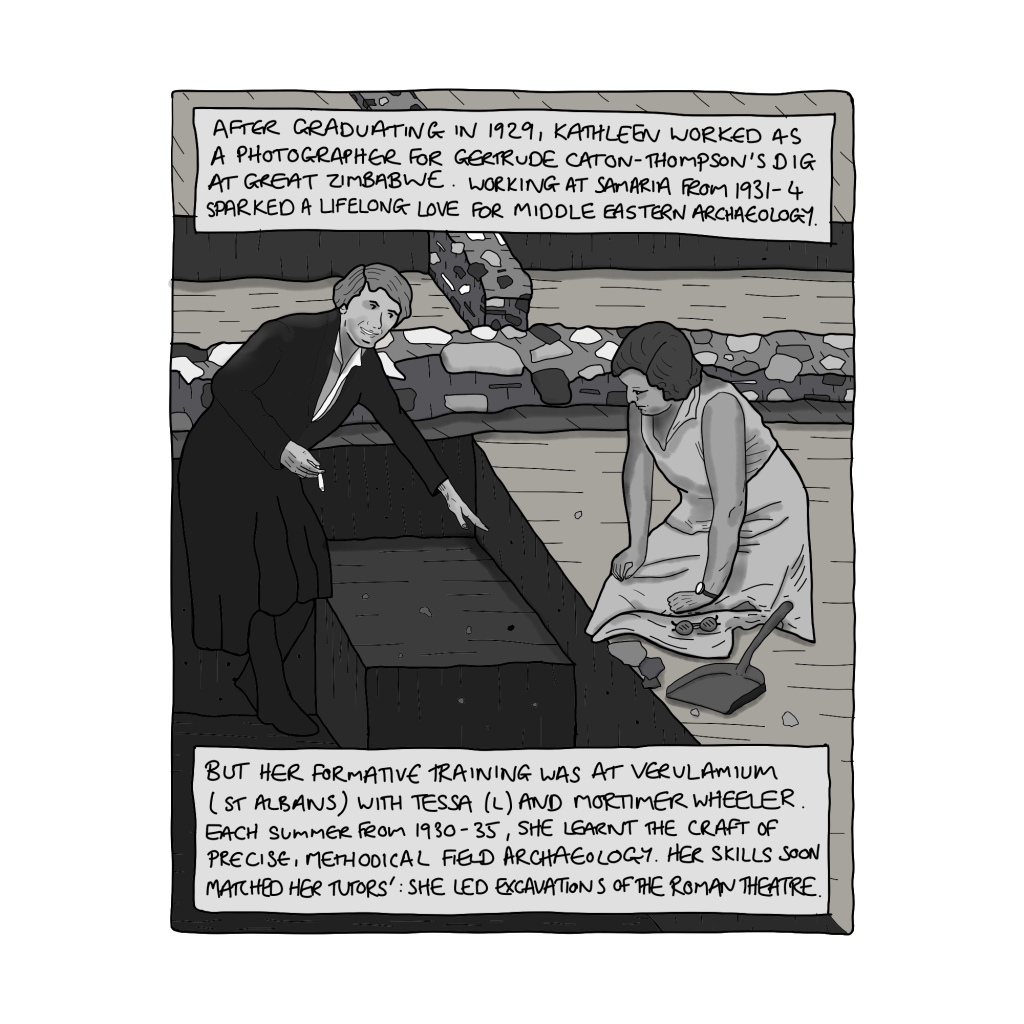

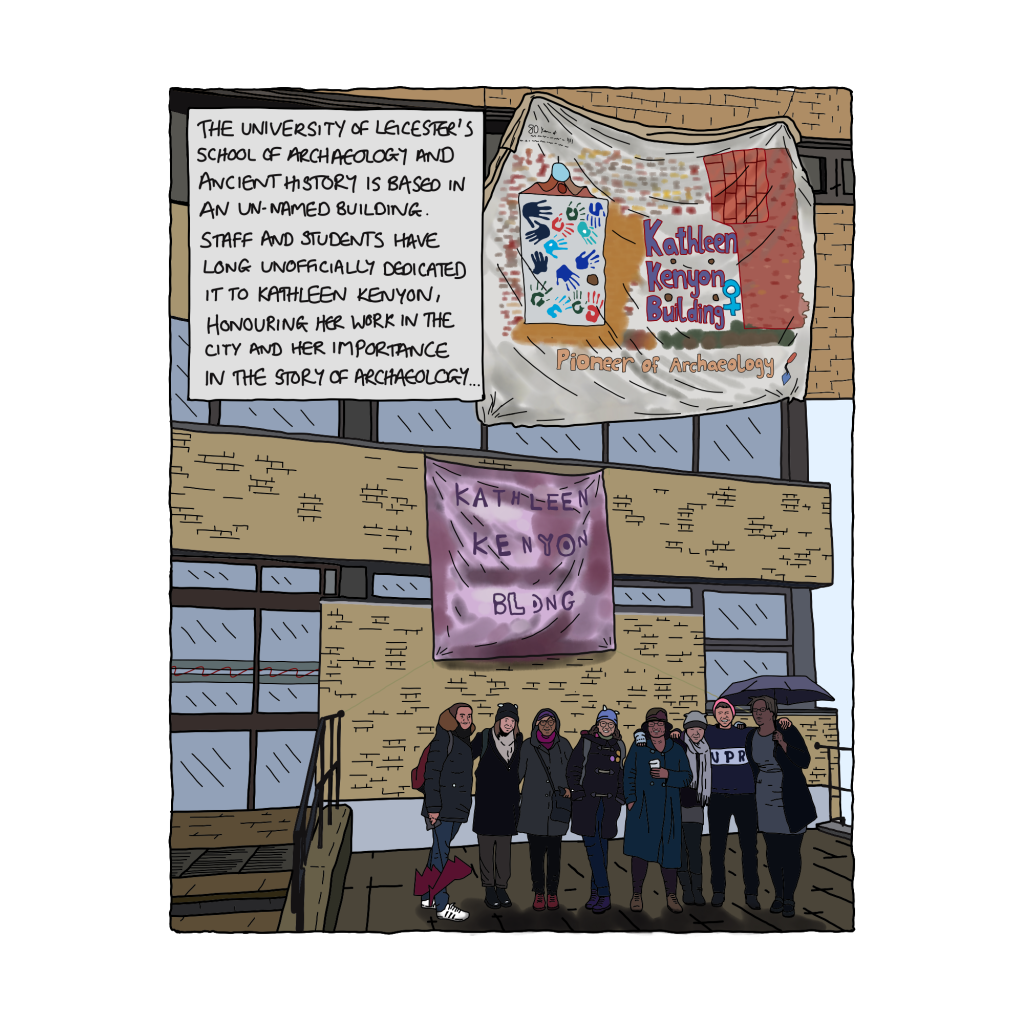

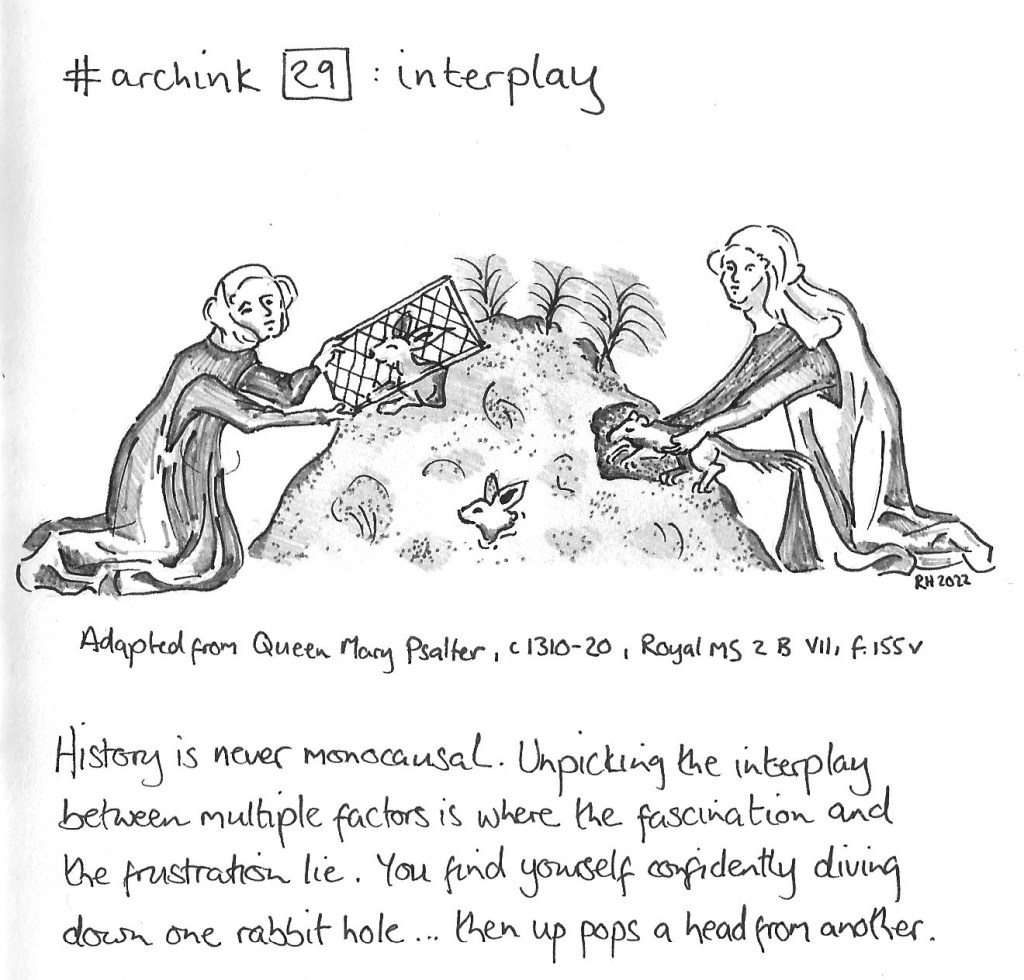

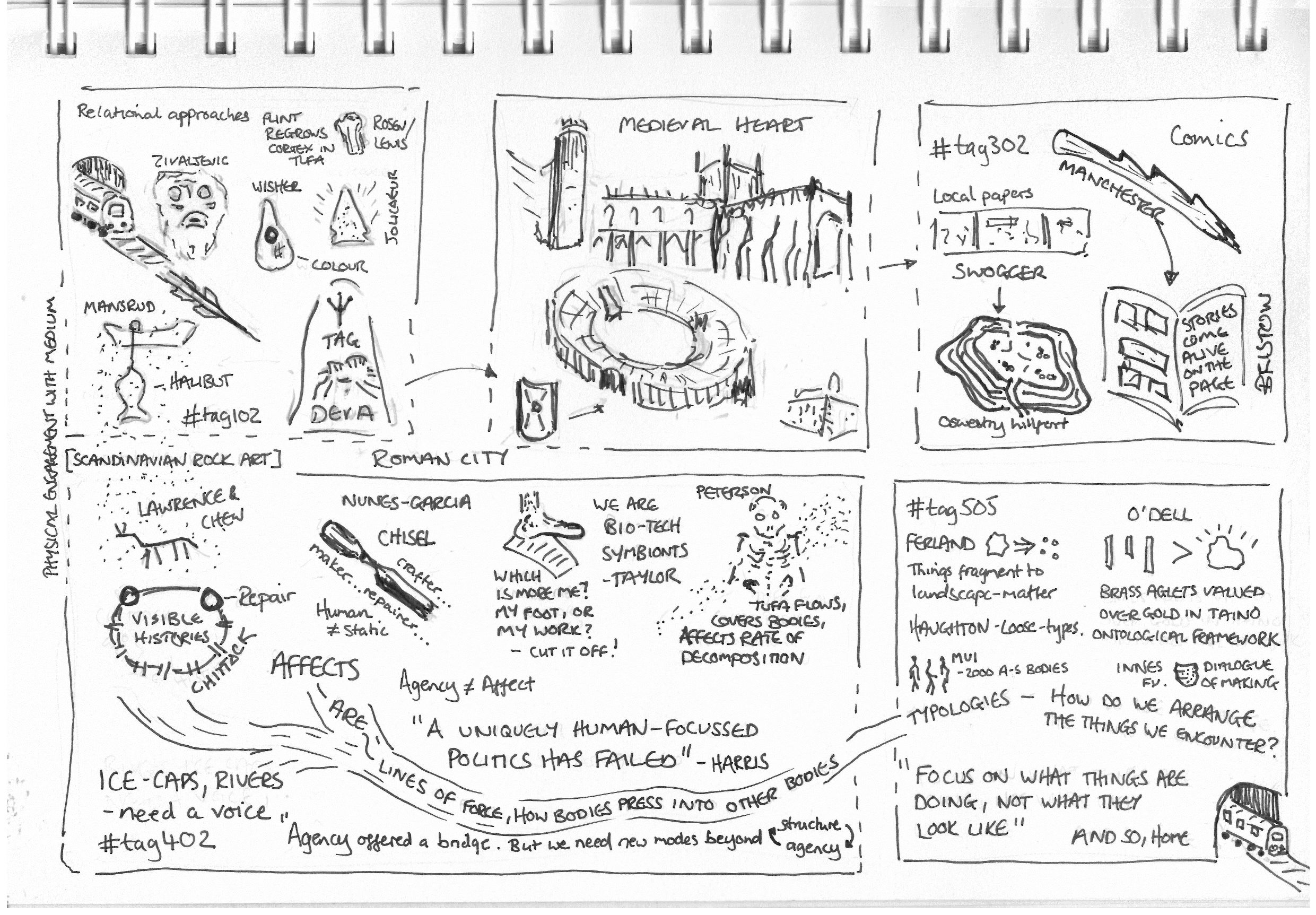

Cartoon summary of my TAG DEVA experience

So, what’s it about? TAG covers a huge range of topics, and every period from deep prehistory to the far future. It aims to take a critical look at the theory that lies behind what we do, and how we do it. Archaeological theory is sometimes considered by many students and practitioners of archaeology to be bewildering at best, and downright impenetrable at worst. There’s also often a perception that we’re still locked in the debates of the later 20th century, between the scientific turn of the New Archaeology that emerged in the 1960s and early 70s (processualism), and the post-processual approach that took shape in the 1980s, which acknowledged the subjective nature of all archaeological interpretations.

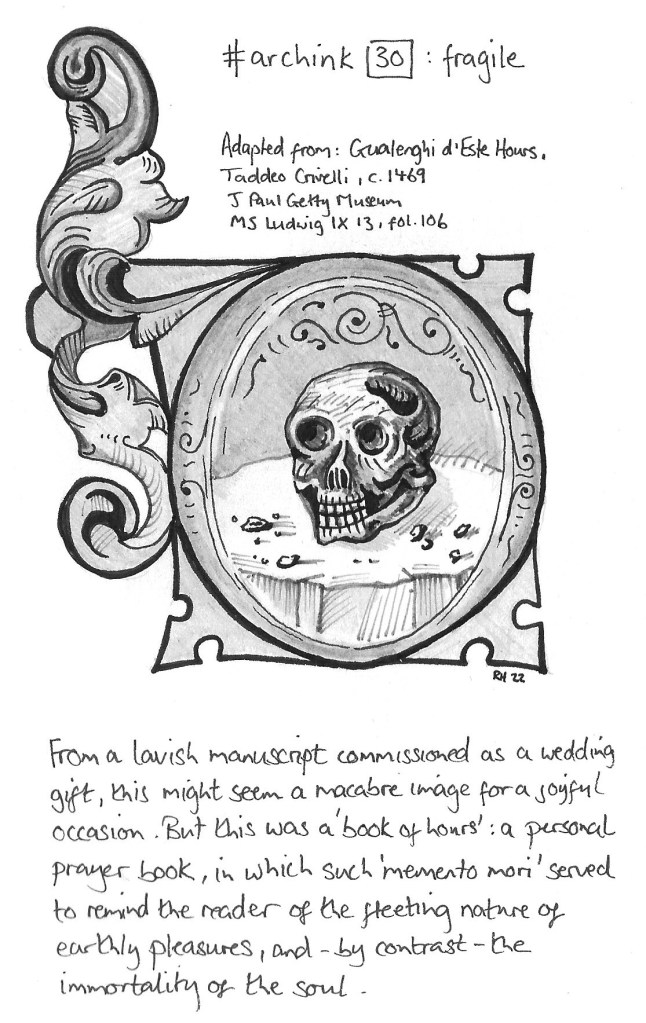

Theory? Arrgh!

Archaeologists’ aversion to theory is compounded, outside of academia, by an assumption that it’s a bitter battleground in which warring tribes hurl lightning bolts between ivory towers, leaving the humble dirt-archaeologist or pot-botherer to go about their business unaffected. But, as one hugely influential archaeological paper (David Clarke’s Loss of Innocence, 1973) famously stated: “practical men (sic.) who believe themselves to be quite exempt from any intellectual influences are… usually the unwitting slaves of some defunct theorist”. Besides, archaeological theory is currently pretty lively, collaborative, and full of fresh and useful ideas.

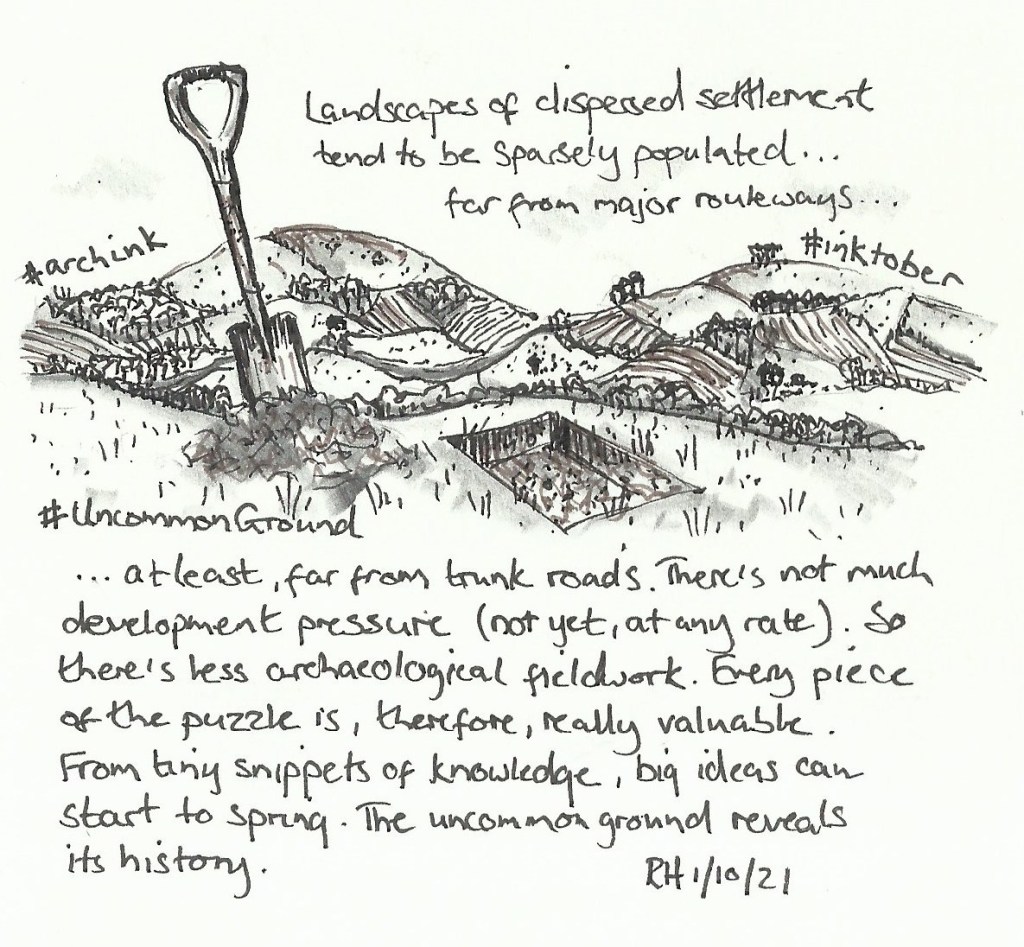

However, it’s difficult to keep up with current debates without institutional access. Most archaeologists working outside of academia — in developer-funded fieldwork, or local authorities — do not have access to relevant academic journals, and find it tricky to take time out to go to conferences. Employers are sometimes happy to subsidise conference attendance for professional development. But TAG is often viewed with suspicion – perceived as lacking practical relevance. As conferences go, TAG is great value; even so, faced with funding it themselves, and attending in their own time, many colleagues are put off.

What are they missing? Well, the theoretical debates that most interest me at the moment are centred around what has been variously described as the ontological turn, or the material turn. Approaches under these banners are often described as relational, or post-human. I’ve written previously about one of these, commonly known as New Materialism. But that’s just one of a number of related theoretical perspectives. What they all have in common is an acknowledgement that if we really want to say something useful about how humans have lived, and the worlds that we have inherited, we have to dismantle the blinkers imposed by the way we see the world.

For the last few hundred years, in the West, our ideas about being and existence have been shaped by dualisms: mind vs. body, nature vs. nurture, natural vs. artificial, genetic vs. environmental, human vs. animal, reason vs. emotion, head vs. heart, sacred vs. profane… dualisms are everywhere. And they’re not very helpful. The world is more complicated than they suggest. Tim Taylor’s paper explored the way that we become products of our own technology: “bio-tech symbionts”. I’m soon to have an operation to reconstruct my knee, using a complex mix of organic materials and manufactured parts. Where, then, will I draw the line between which parts of me are natural, and which are artificial? The two work in tandem; neither will function without the other. Besides, consider every other ‘artificial’ mechanism by which I’ve survived and grown to date: medications both organic and synthetic, or both; technology through which I’ve learnt, produced, been diagnosed… the separation of elements into dichotomies like ‘natural’ vs ‘artificial’ doesn’t work. So, how can we find a framework for looking at systems involving human behaviour without falling back into comforting binary oppositions?

Agency

Towards the end of the last century, practice theory and the concept of agency were harnessed to archaeological theory. Agency is the ability to have an effect, to modify or reinforce a set of relationships or state of affairs. It is not just confined to humans, nor to living things: objects can be assigned agency, too. Agency is locked in a continuous feedback loop with the structure of the system within which the agents exist, leading to cultural reproduction – the ways in which systems are maintained or adapted over time.

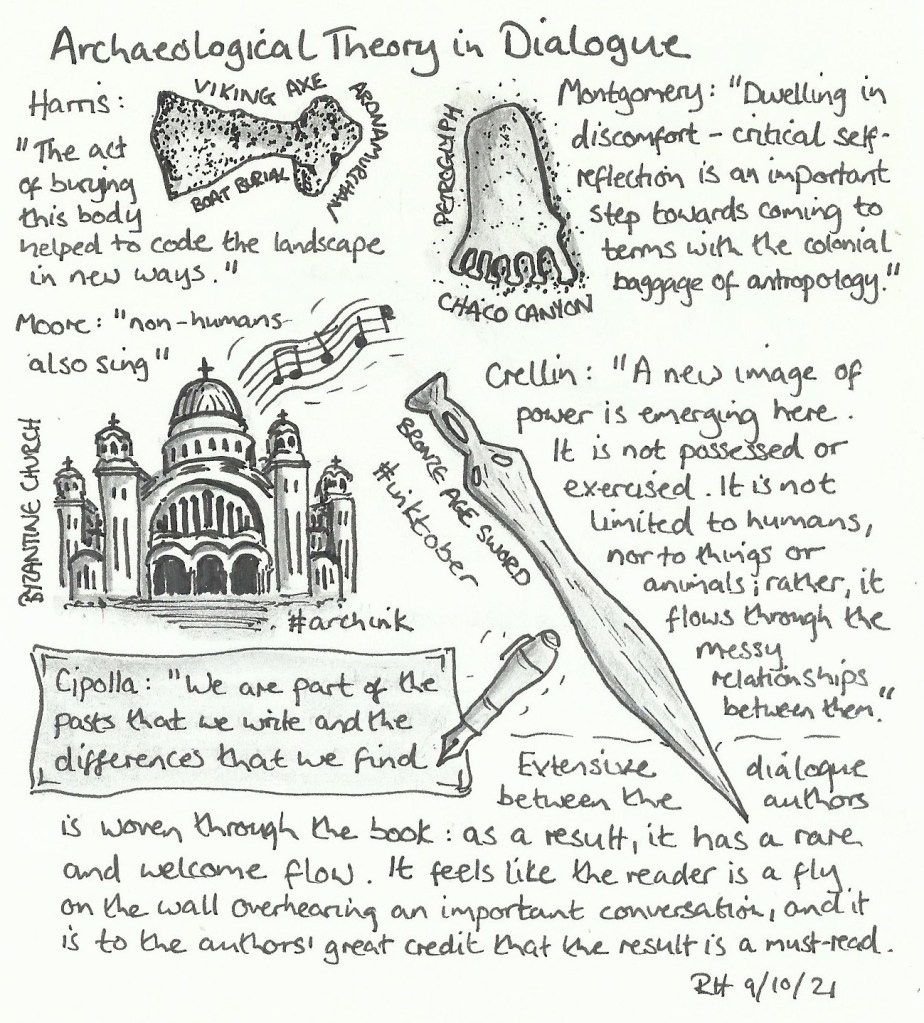

Agency has, in one way or another, influenced pretty much all of the major trends in archaeological theory over the last 20 years. I can’t hope to do those debates justice in a blog post, but Oliver Harris and Craig Cipolla provide a brilliant, infectiously accessible summary of these in their recent book: Archaeological Theory in the New Millenium. If you got lost at post-processualism, or never caught the theory bug, do read their book. In fact, read it anyway: I love theory and it still taught me loads.

One of my undergraduate theory teachers was John Robb. He and Marcia-Anne Dobres edited the book on agency in archaeology. It’s been a formative and hugely influential concept for me. But I do have to admit that it’s a counter-intuitive concept to grasp. Maybe the term carries too much cultural baggage, and leads us too readily to anthropomorphise.

Perhaps it’s just that I’m not good at explaining it, but it’s sometimes too forceful, too deliberate. I’m typing this on my phone, when I should be going to sleep. Does my phone have agency? Undoubtedly – too much. But what about the mug on the table beside me? Well, yes, but it’s more subtle. That mug is special, made by my favourite potter, in a place that means a lot to me. I have had it for almost 10 years. It is only used for my last drink of the evening. The mug, in that way, habituates me. But to say it has agency implies a certain direct force, which risks flattening the nuanced mesh of relations between objects, places, and people, through which my interactions with the mug are governed.

Beyond Agency

As Oliver Harris pointed out in his paper, a quirk of the English language is that the very expression ‘object agency’ seems an oxymoron: an object is something acted upon. But our understanding of the importance and vulnerability of fragile, interconnected environmental and social systems increases almost as fast as their degradation plunges us towards ecological and political instability. We are linked, networked, enmeshed: however you wish to phrase it, humans are inextricably involved in the world around us, as we have always been.

So it was interesting to see a number of approaches explicitly moving beyond Agency, to consider ways in which — starting from a level playing field, or flat ontology — we can better examine the role of non-human things. Helen Chittock, discussing wear, repair, and composite artefacts in later prehistory, talked about the “conspicuous accumulation of visible histories”. The concept of Affect, introduced by Harris, is one promising tool; ‘Affect’ can be imagined as lines of force, describing how bodies — both human and non-human, living and not — press into other bodies.

Variety

Another great session explored relational approaches to studying the worlds inhabited by hunter-gatherers, with some breath-taking case studies. Ivana Živaljević told of the shimmering cloaks of fish teeth, mirroring the pearly appearance of the spawning Danube-traversing Black Sea roach (Rutilus frisii), donned by the Mesolithic inhabitants of the Iron Gates Gorge; Izzy Wisher spoke on Palaeolithic beads made from perforated deer teeth; Anya Mansrud on halibut-fishing in Mesolithic Norwegian rock art; and Worcester’s Caroline Rosen and Jodie Lewis looked at the significance of a tufa spring to the people and animals who returned to it across 2000 years.

A lively session on approaches to typology brought a fresh focus to a tired topic: every paper was concise, thoughtful, and well-delivered. It challenged us to not only consider the groups to which archaeological objects might belong, but also where they sit in a process of change: to look at what things are doing rather than what they resemble.

There was a wealth of other sessions on offer, too: on public heritage, feminist archaeologies, the nature of expertise… the range is always broad.

Creative comics

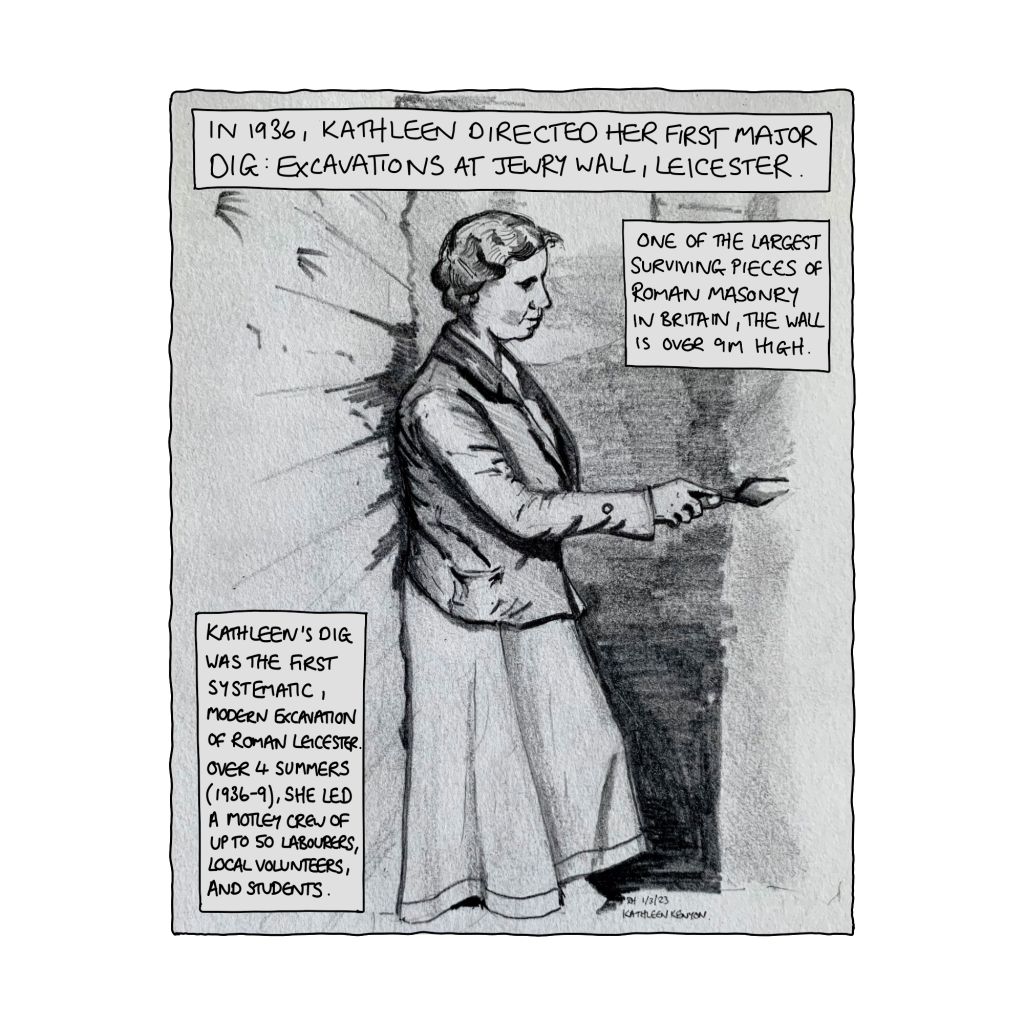

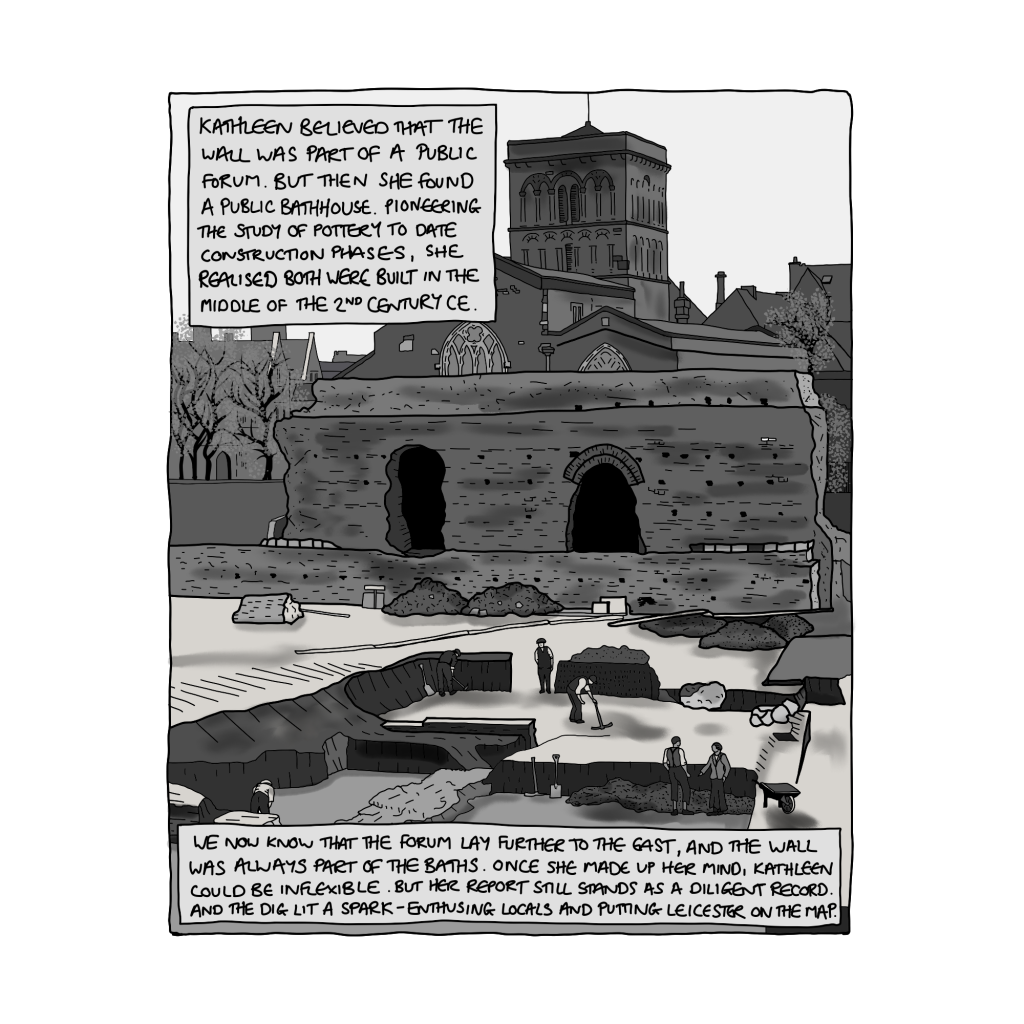

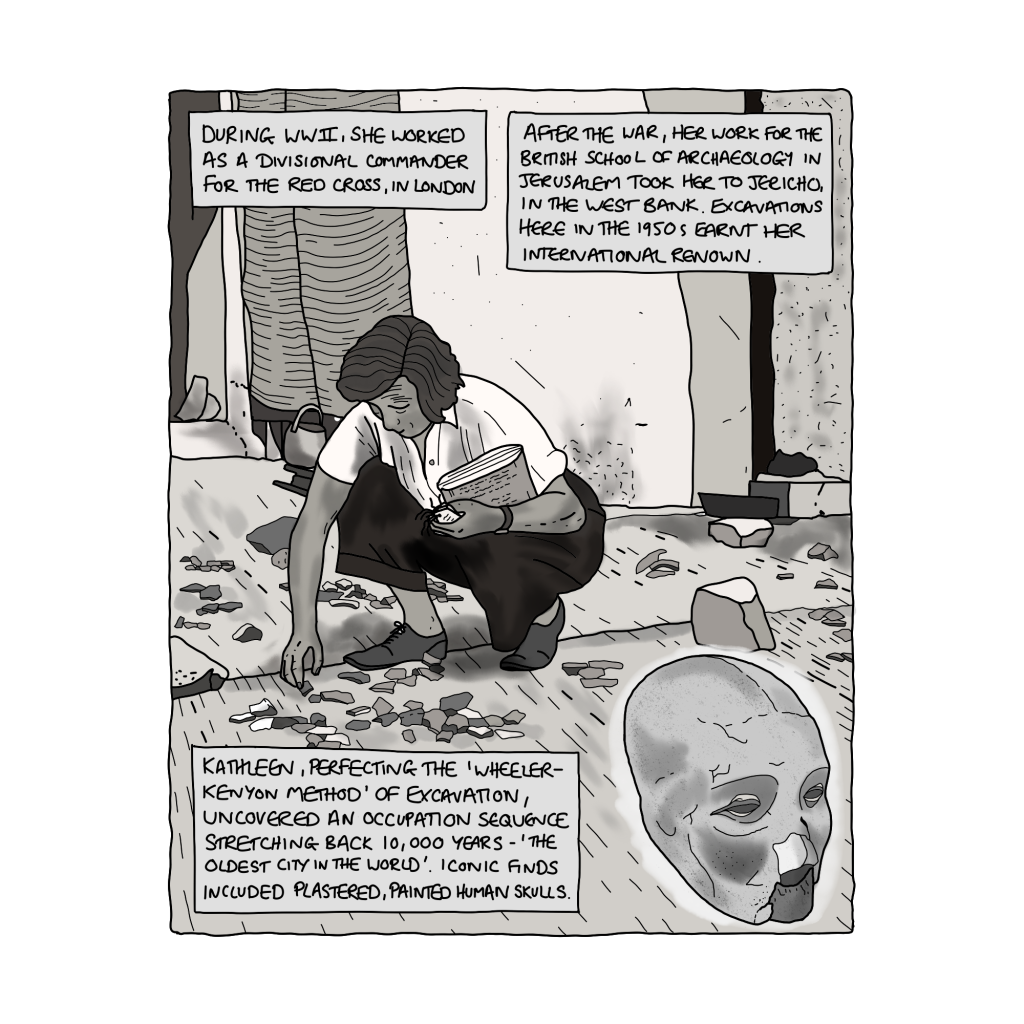

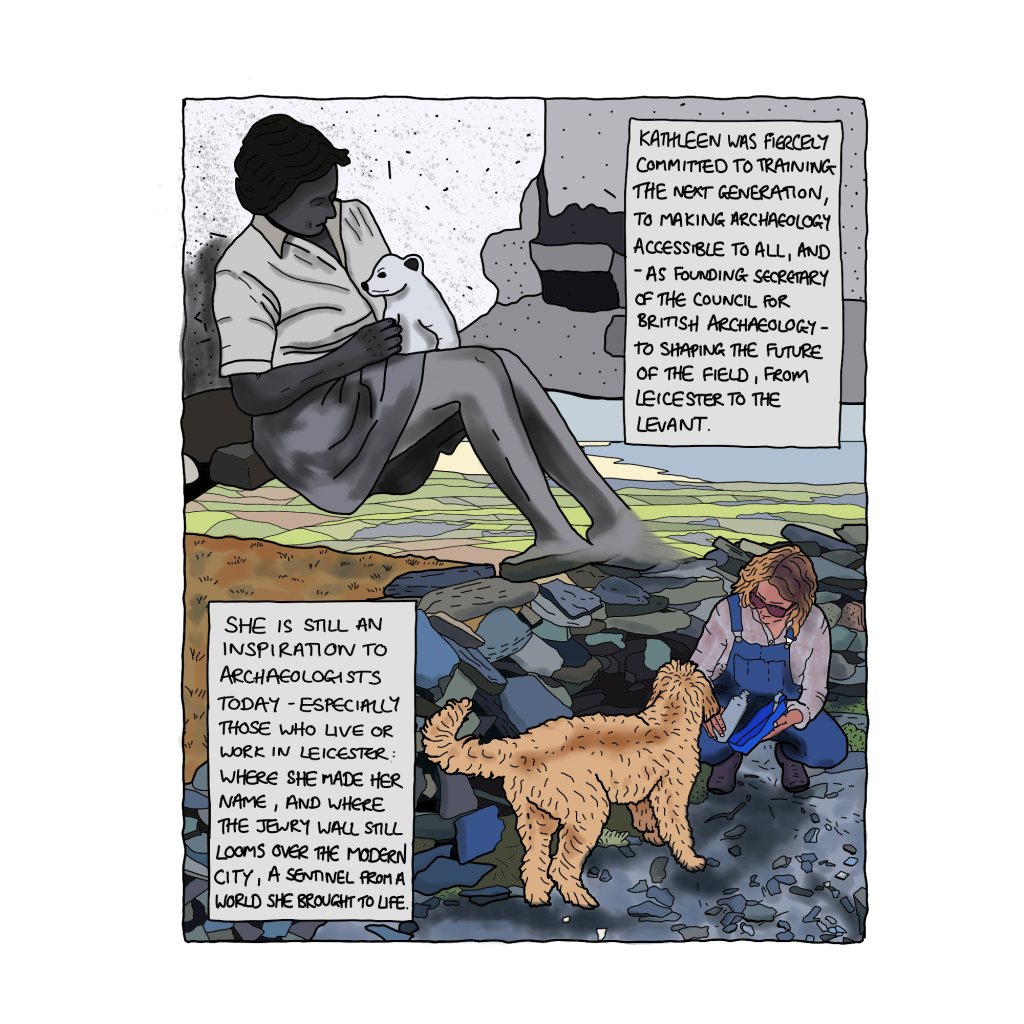

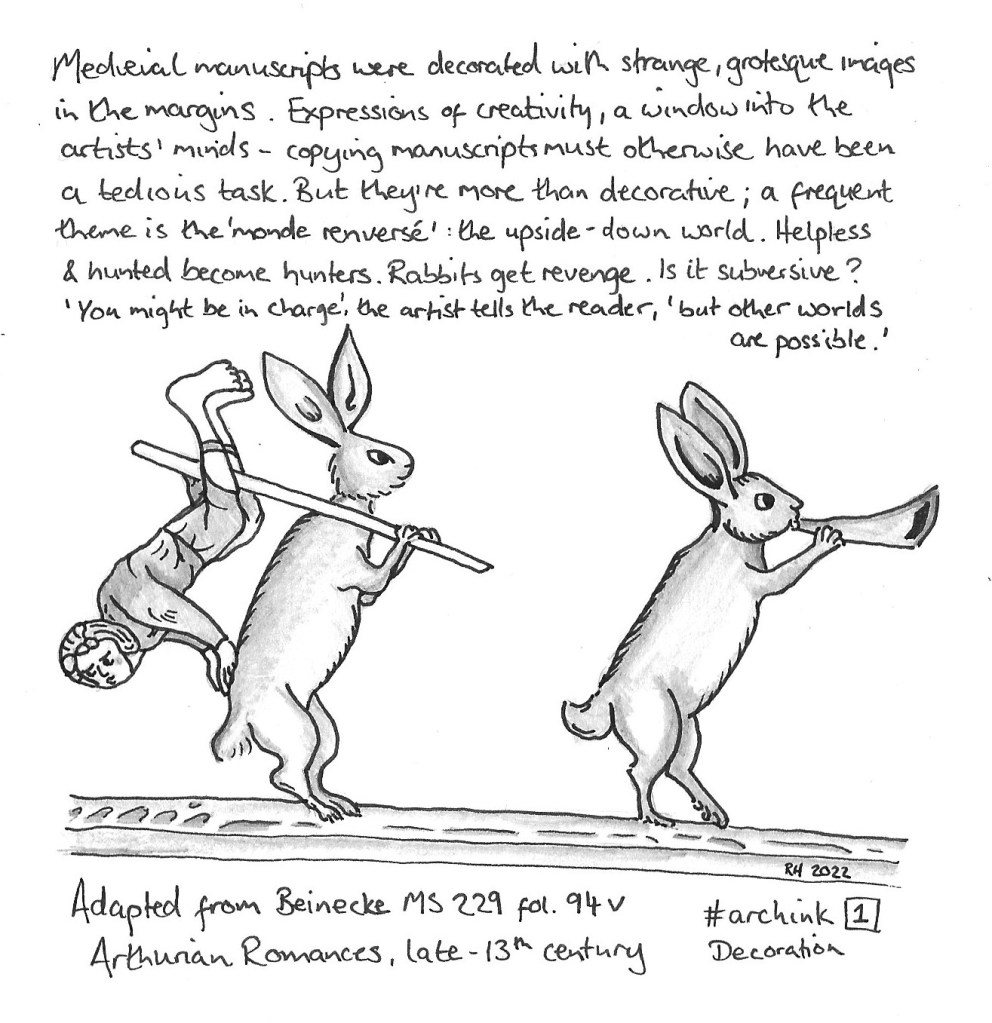

But the highlight of TAG, for me, was a session organised by John Swogger on Comics, Communities, and the Past. Some great case studies from Magic Torch Comics, John himself, and the University of Manchester got our imagination fired up, then as we heard the story of a Mesolithic barbed antler point from the Manchester team, we were encouraged to live-sketch a comic.

Mine began with the deposition of the point in a shallow lake in spring. A deer comes to drink from the lake, absorbing the power of the tool. Later the deer sheds its antlers, which are recovered, transformed into another barbed point for winter fishing expeditions, before the cycle is begun again with another deposition.

15-minute cartoon: Life-cycle of a Mesolithic barbed antler point

It was a thoroughly inspirational session, and inspired me to while away a couple of hours on the train home with my own version of the conference in comic-form. Aside from the difficulties of sketching on antiquated clattering carriages and freezing platforms, it was an enjoyable way to recall and process.

TAG is at UCL, London, on the 16th – 18th December this year. If you’re able to attend, it’s well worth going. It’s a gathering of people who share a passion for shining a light under the dark rocks of archaeological practice, and casting a critical eye over what lies beneath. TAG is a tribe: a maddening, provocative, welcoming, brilliant assemblage, and one I’m glad to experience.

53.193392

-2.893075